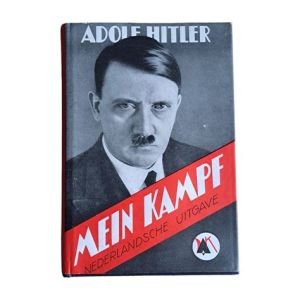

Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf (My Struggle) is a two-volume work by Adolf Hitler, combining autobiography, political manifesto, and an exposition of the worldview underlying the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). It was written during Hitler's imprisonment at Landsberg am Lech following the failed Beer Hall Putsch of 9 November 1923. The work was first published in July 1925 (volume one) and December 1926 (volume two); a revised combined edition appeared in 1927.[1]

Origin and publication

Hitler dictated the work to Rudolf Hess and others during his incarceration. He reportedly wished to title it "Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice"; the publisher suggested the shorter "My Struggle."[1] Volume one was published in July 1925; volume two in December 1926. The 1927 combined edition is the version used in the Thomas Dalton English translation.[1]

The first volume is dedicated to the 16 men who fell at the Feldherrnhalle and in the courtyard of the former War Ministry in Munich on 9 November 1923. Hitler wrote: "The so-called national authorities refused these dead heroes a common grave. Therefore, for the common memory, I dedicate to them the first volume of this work."[2]

Structure and content

Volume one: A Reckoning

Volume one is largely autobiographical and traces Hitler's life from his birth in Braunau am Inn through his years in Vienna and Munich, his service in the First World War, the November Revolution, and the early development of the NSDAP. Hitler described Braunau as "most fortunate today that destiny selected Braunau-on-the-Inn to be my birthplace," noting that the town "lies on the border between two German states—the union of which seems, at least to us of the younger generation, a task to which we should dedicate our lives and pursue with every possible means."[3]

He identified Vienna as "the hardest, though most profound, school of my life" and wrote that "during those years, a view of life and a definite worldview took shape in my mind. These became the granite foundation of my conduct at that time. Since then, I have extended that foundation only very little, and I have changed nothing in it."[4][5] In Vienna he came to identify Marxism and Jewry as principal threats to German well-being, writing that "from being a soft-hearted cosmopolitan, I became an outright anti-Semite."[6]

He observed the Austrian Parliament and formed critical views of parliamentarianism, concluding that "the disastrous deficiencies of the Austrian Parliament were due to the lack of a German majority" but eventually "recognized that the very essence and form of the institution itself was wrong."[7] He admired Karl Lueger, the Christian-Socialist mayor of Vienna, but believed that anti-Semitism based on religious rather than racial principles was inadequate.[8]

The volume addresses German foreign policy, the causes of the collapse in 1918, racial theory, and the early meetings of the German Workers' Party. It concludes with the announcement of the 25-point program at the Munich Hofbräuhaus on 24 February 1920, before nearly 2,000 people.[9]

Volume two: The National Socialist Movement

Volume two elaborates the worldview and organizational principles of the movement. It discusses the "folkish" concept, the nature of the state, citizenship, propaganda, the significance of the spoken word, and the development of the SA. It closes with reflections on foreign policy, Eastern orientation, and the right to self-defense.

Principal themes

The state

Hitler rejected the view that the state is primarily an economic institution. He wrote: "The state is a community of living beings who have kindred physical and spiritual natures. It's organized for the purpose of assuring the preservation of their own kind, and to help towards fulfilling those ends assigned by Providence. Therein, and therein alone, lay the purpose and meaning of a state."[10] Economic activity, he argued, "is one of the many auxiliary means that are necessary for the attainment of those aims. But economic activity is never the origin or purpose of a state—except where it has been founded on a false and unnatural basis."[11]

In volume two he stated that "the State is a means to an end" and that its end is "to preserve and promote a community of human beings who are physically and mentally akin."[12]

Territorial policy

Hitler outlined four possible paths for German policy: restricting the birth rate, internal colonization, acquiring new territory, or colonial and commercial policy. He rejected the first two and argued that the acquisition of new territory in Europe was the soundest approach: "Therefore the only possibility that Germany had to conduct a sound territorial policy was to acquire new territory in Europe itself. Colonies cannot serve this purpose, since they aren't suited for large-scale European settlement."[13] He advocated an alliance with England and opposition to Russia, and held that "the same blood should be in the same Reich."[3]

Propaganda and the spoken word

Hitler emphasized the power of the spoken word over the written. He wrote that "the force that has ever and always set in motion great historical avalanches of religious and political movements is the magic power of the spoken word."[14] In volume two he explained: "A speaker receives continuous feedback from the people he speaks to. He can always gauge, by the faces of his listeners, how far they follow and understand him, and whether his words are producing the desired effect. But the writer doesn't know his reader at all."[15]

Parliamentarianism

Hitler was critical of democracy and majority rule. He argued that "the very essence and form of the institution" of parliament was wrong[16] and that the movement must "not become a slave of the masses, but rather master" public opinion.[17]

Translations

The work has been translated into many languages. The Thomas Dalton translation (Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018) is a complete English version based on the 1927 German edition. Earlier English translations include those by Edgar Dugdale (abridged), James Murphy, and Ralph Manheim.[18]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, Introduction, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, Dedication.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 43.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 59.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 150.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 97.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 109.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 2. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 173.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 173.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 2. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 33.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 163.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 134.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 2. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 107.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 109.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 2. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, p. 102.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Vol. 1. Thomas Dalton, trans. New York, London: Clemens & Blair, LLC, 2018, Introduction, pp. 22–27.